The Synoptic Dilemma: Explaining the Divorce Exception Clause

This paper was originally written by Colin on July 31, 2022

THE SYNOPTIC DILEMMA: EXPLAINING THE DIVORCE EXCEPTION CLAUSE

A concerned man looking for counsel shared in an email that, “My wife and I are both divorced. Her ex-husband is still alive; however, my ex-wife has passed away. We are very concerned about the issue of whether or not we are living in adultery, as it seems Jesus teaches...”[1] He went on to say people in his church “…insist that the only way for us to escape living in adultery is to divorce one another and remain unmarried...I can't honestly see how another divorce could make things right.”[2] How Jesus’s teachings on divorce are interpreted and applied determine the counsel this man receives and the decision he and his wife make.

In both Mark 10:11 and Luke 16:18 Jesus said if a man “divorces his wife and marries another, he commits adultery.”[3] However, Matthew records Jesus saying similar phrases but with the qualification, “except for sexual immorality,” (5:32,19:9). The problem this essay addresses is why are Mark and Luke’s account missing the exception for sexual immorality whereas Matthew includes it? Do they contradict? Is the exception valid and why? This essay will seek to establish that: the exception in Matthew is valid, the synoptic gospels can be understood cohesively, and there arelegitimate reasons related to historical context as to why Mark and Luke omitted the exception and why Matthew included it. This thesis aligns with the majority of modern evangelical scholarship.[4] Determining whether the exception clause was original to Jesus is not required for this thesis to be correct.[5]

DIVORCE FOR SEXUAL IMMORALITY WAS NOT BEING DEBATED AND IT WOULD HAVE BEEN ASSUMED

Divorce on the grounds of sexual immorality (such as adultery) was commonplace during Jesus’s ministry both for Gentiles and Jews.[6] In Matthew 19:3, Pharisees asked Jesus, “Is it lawful to divorce one’s wife for any cause?” (emphasis mine). The Pharisees did not ask whether divorce is ever lawful. They asked if divorce for-any-reason was lawful. Jesus’s answer is to a specific question in a specific context. The Pharisees appropriately asked that question because it was the current debate of the time, which was between two Jewish rabbinical schools, Shammai versus Hillel (both Pharisees), and their differing interpretations of Deuteronomy 24:1.[7] “Followers of Hillel,” according to Heth, “placed no limit whatsoever on the Jewish husband’s unilateral right to divorce his wife. The Shammaites, on the other hand, focused on the word ‘indecency’ in the phrases in Deuteronomy 24:1 and limited the husband’s right of divorce to ‘adultery.’”[8] The Hillelite view gave permission to divorce for any reason, even for something as trivial as a sub-par lunch.[9]

During the time of Jesus’s ministry, both Shammaite and Hillelite (Hillelite was newer at the time) divorces would have been available for Jews, with little doubt amongst scholars that Hillelite divorces became the most popular by the end of the first-century if not already by 70 C.E.[10] Instone-Brewer’s well-respected work finds not only was the Hillelite any-cause divorce most popular during Jesus’s time, but it became the only divorce available at all in post-70 C.E. Judaism because of the disappearance of Shammaites related to the destruction of the temple.[11] Because Hillelite divorces were likely the only divorces available after 70 C.E., people over time simply got divorced for any reason without recognizing the triviality’s source was related to the Hillel distinction.[12] These details matter because they impact why the gospel writers made the authorial decisions they did, which in turn solves the synoptic dilemma.

Mark’s audience would have been more familiar with the Shammai-Hillel debate whereas it is possible Matthew’s audience would have been completely ignorant of key debate-related phrases especially after the destruction of the temple.[13] Mark has the Pharisees asking Jesus “Is it lawful for a man to divorce his wife?” (10:2). Notice how “for any cause,” is omitted from Mark 10:2 but included in Matthew 19:3. Mark’s audience would have mentally added “for any cause,” after the question “is it lawful to divorce your wife?” because the question made no sense without it.[14] There would have been no point in Pharisees asking, “is it lawful to divorce a wife in general?” because according to Deuteronomy 24:1 the answer to that question was, ‘Yes, it says so in the Law.’”[15] The Pharisees were asking Jesus whether he agreed with Shammai or Hillel, not asking him whether divorce was ever permissible in a general. If Jesus would had replied “yes” to the Pharisees’ question, he would have sided with Hillel.[16]

Just as Mark omitted “for any cause,” he also omitted the exception clause for the same reason. When Mark’s audience read the prohibitive clause, they would have mentally added something to the extent of “except for valid grounds.”[17] They knew divorce in general was not being debated; any-cause Hillel divorce was. When they heard Jesus say the prohibitive clause, it would not have been taken as an exceptionless absolute, but as a specific rebuke to the Hillelite position, and they would have assumed the divorce exception related to sexual unfaithfulness via Deuteronomy 24:1.[18]

Such assumptions are common elsewhere in the Bible and in culture. For example, “except for his wife” is mentally added after one reads “…everyone who looks at a woman with lustful intent has already committed adultery with her in his heart,” in Matthew 5:28.[19] Similarly, it is unlawful to drive 10 mph on the highway when the speed limit is 70 mph, but it is assumed to be okay when there is a traffic jam or when there is bad weather such as a blizzard.[20] Sometimes exceptions are assumed because they are obvious. When an exception is obvious, the exception doesn’t have to be explicitly spoken because it will be assumed. “…Mark and Luke did not include Jesus’s statement of this exception because there was no dispute about it and everyone agreed that it was a legitimate ground for divorce.”[21] Matthew on the hand, being the thoughtful historian that he was, added “for any cause,” in 19:3 and added the exception clause in 19:9 “…for the sake of his readers who were no longer entirely familiar with the terms of this debate within rabbinic Judaism.”[22] Matthew’s decision to insert those phrases helps his readers understand Jesus’s strong stance against divorce and for life-long committed marriages.

THE PROHIBITIVE CLAUSE IS HYPERBOLE AND GENERALIZATION

Legitimate reasons have been provided for why the exception clause is missing from Mark and Luke compared to Matthew, but there is need to classify exactly what the prohibitive clause is. Such clarity is warranted because the prohibitive clause is interpreted by those in the minority view as a literal absolute without exception.[23] If it is not to be taken literally, then an alternative explanation and purpose for the prohibitive clause must be made. Evangelical scholars defending the validity of the exception clause define the prohibitive clause in one of two ways. Keener and Stein define the prohibitive clause as intentional overstatement (hyperbole), whereas Heth, Carson, and Blomberg would define it more as Blomberg puts it, “a generalization which admits of certain exceptions.”[24] The commonality between the two (hyperbole and generalization), is that both assume exceptions.

Hearing that Jesus taught using hyperbole can be odd for some, so it is worth explaining more. For Stein, hyperbolic overstatement was one of many techniques including metaphors, proverbs, similes, and puns, Jesus used to establish principles while teaching.[25] The fact Jesus used hyperbole should not be cause for alarm since Jesus is found to use hyperbole throughout the gospels and even in the context leading up to Jesus’s teaching on divorce in Matthew 5.[26] Jesus’s commandment to tear out one’s right eye and cut off one’s right hand (Matthew 5:29-30) to avoid lust is hyperbolic.[27] If it is not, then why do Christians have intact eyes and hands? The strength of Keener’s argument, however, is in showing how if one is to take the prohibitive clause literally, then one concludes marriage is indissoluble which leads to daunting implications.[28]

If the prohibitive clauses are taken literally, then everyone who remarries after divorce (regardless of the cause of divorce) is actively committing adulterous marital relations and constantly committing emotional unfaithfulness.[29] The adultery can only be explained by concluding “…in God’s sight one or both members of the remarrying couple remain married to their original spouse.”[30] And the next logical solution then would be for churches and pastors to assist in breaking up the new adulterous couple and to reunite the original couple who is still married.[31] Few churches and pastors are willing to do such things and wisely so.

So, is it best to define the prohibitive clause as hyperbole or as a generalization? It appears they may be one in the same and it comes down to preference of language. Heth thinks the exposition for both hyperbole and generalization “is essentially the same under each category,” but he goes on to conclude, “…I just think words like ‘exaggeration,’ ‘hyperbole,’ and ‘rhetorical overstatement’ convey the wrong idea.”[32] Keener similarly suggests New Testament exceptions point readers to principles that guide in extreme situations.[33] Hyperbole and generalizations (guiding principles) can be thought of as in the same vein because they both communicate a strong message while both assuming exceptions. Just as hyperbole isn’t meant to be taken literally all the time, a general principle such as “if you divorce your spouse and marry another, you commit adultery,” is not meant to be taken as an exceptionless absolute. A general principle is a general principle. An exception to a general principle does not negate the general principle.[34]

OTHER CONTEXTUAL REASONS FOR THE EXCEPTION CLAUSE

One final misconception about the exception clause that one may still have is it gives license to or endorses divorce. The historical context behind the Pharisees’ question in Matthew 19:3 however, suggests it is clear that Jesus was directly addressing and rebuking the Hillelite position, which would of had a “tightening effect in morality of the church.”[35] Hence, the disciples shock in Matthew 19:10. Only just-cause (sexual immorality) divorce was permitted, a much more “stringent” stance compared to the Pharisees and the Mishnah.[36] There is a difference between recommending or mandating divorce versus permitting it. Just because Jesus permitted divorce does not mean Jesus approved of it.[37]

First-century Jews had turned Deuteronomy 24:1-4 into mandatory divorce if a wife was unfaithful, prohibiting the husband from taking back his unfaithful wife.[38] This is evident by the question the Pharisees asked Jesus in Matthew 19:7 after Jesus had referenced the Genesis one-flesh union. They asked, “Why then did Moses command one to give a certificate of divorce and to send her away?” (Matt.19:7 emphasis mine). Jesus’s response indicates a clear correction by indicating Moses conceded rather than commanded (Matthew 19:8). Moses did not command divorce but allowed them to divorce.[39] Hardness of heart (sin) is what caused their desire to divorce, and possibly also caused their desire to prevent reconciliation.

“If Jewish law mandated divorce for sexual unfaithfulness and prohibited a wife from ever returning to her husband after she had been unfaithful,” Heth explains, “Jesus may be countering both of these notions via the exception clause, which would permit divorce for immorality and might even encourage offended spouses to forgive and take back unfaithful mates.”[40] Hearing they are not commanded to divorce an adulterous wife and only permitted to would have implied a marriage could be kept together despite sexual unfaithfulness, certainly adding to the shock (verse 10).[41] In other words, Jesus permitted just-cause divorce not to encourage Christians to divorce, but more so to ensure the innocence of the victim if the marriage was irreparable after attempts to reconcile. Keener says it another way: “The two explicit biblical exceptions, adultery and abandonment, share a common factor: they are acts committed by a partner against the obedient believer. That is, the believer is not breaking up his or her marriage but is confronted with the marriage covenant already broken.”[42] The entire notion of being an obedient believer and taking back a sexually unfaithful spouse if he or she repents, could certainly be an intended effect of the exception clause as Heth suggested.

CONCLUSION

Rather than conclude Matthew contradicts Mark and Luke, an alternative explanation has been summarized showing that the synoptic dilemma can be cohesively solved simply by understanding historical context. First, divorce on the grounds of sexual immorality was not being debated in the context of the synoptic passages because popular trivial divorce (Hillel) was, which Jesus strongly rebuked. Mark and Luke knew their readers would been more familiar with this context so they found no reason to include phrases like the exception clause because the phrases would have been assumed. It made more sense for Matthew to include the clause because his audience would have been unfamiliar with backdrop of the Hillel-Shammai debate. Second, because the prohibitive clause was not meant to be an exceptionless absolute, it is more than fair to define the prohibitive clause as hyperbole and generalization. Both achieve the same goal. Third, there would have other additional contextual reasons for the exception clause to be valid. These reasons include reducing sinful rampant divorce that was going on at the time, introducing the possibility of taking back an unfaithful spouse, and protecting the innocent spouse from incurring sin they did not commit. With all of this said, an apt reminder from Keener brings this essay to a close: “…exceptions must remain exceptional and not the focus, or some will exploit as loopholes for sin our argument originally meant to defend the innocent or to extend mercy.”[43]

[1] David Instone-Brewer, Divorce and Remarriage in the Church: Biblical Solutions for Pastoral Realities (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 2003), 182.

[2] Instone-Brewer, Divorce and Remarriage in the Church. 182.

[3] All quotations of scripture will be ESV unless specified otherwise. Please see Appendix 1 Figure 1.A for the relevant scriptures and definitions of two pertinent terms used in this work.

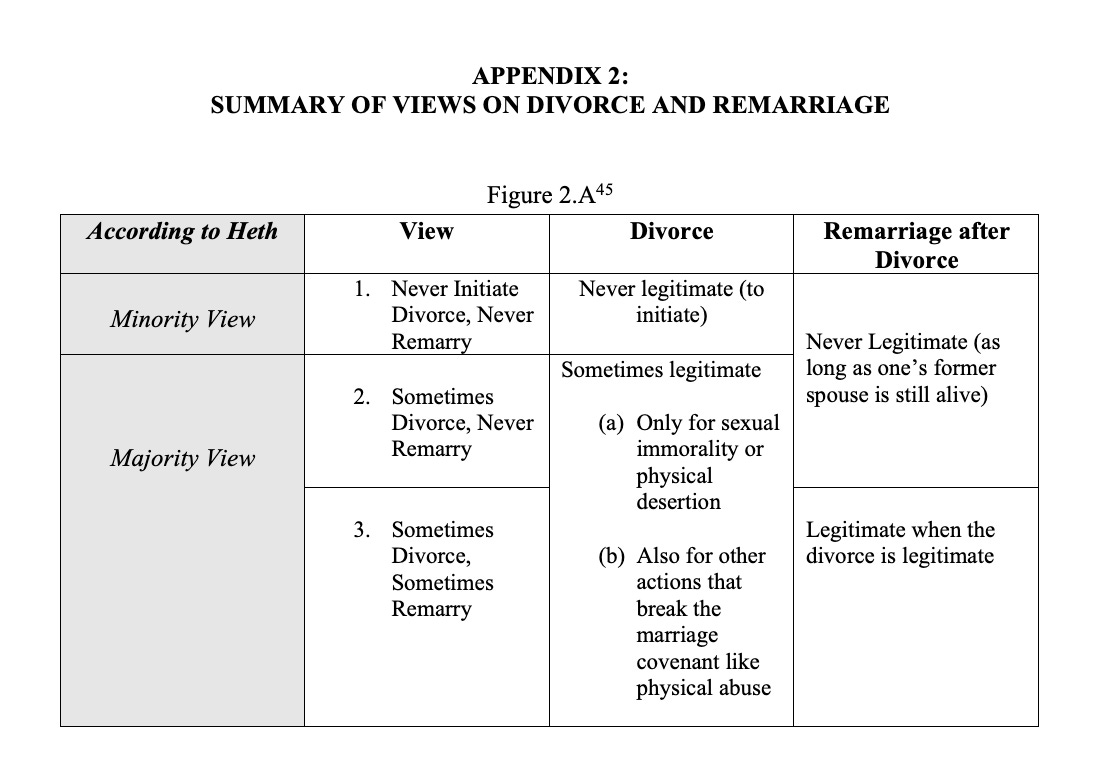

[4] Appendix 2 Figure 2.A outlines differences between majority and minority views related to divorce.

[5] See Appendix 3 for further explanation and for Figure 3.A which outlines the interpretive scenarios regarding originality.

[6] Andrew Naselli, “What the New Testament Teaches about Divorce and Remarriage,” Detroit Baptist Seminary Journal 24 (2019): 24; David Instone-Brewer, Divorce and Remarriage in the Bible: The Social and Literary Context (Grand Rapids: Eerdman’s, 2002), 134.

[7] Intone-Brewer, Divorce and Remarriage in the Bible. 110-13; Craig Keener, …And Marries Another: Divorce and Remarriage in the Teaching of the New Testament (Peabody: Hendrickson, 1991), 38-39; William Heth, “Remarriage for Adultery or Desertion,” in Remarriage After Divorce in Today’s Church: Three Views, ed. Mark Strauss, Counterpoints (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2006), 63-64; Naselli, “What the New Testament Teaches,” 9-10.

[8] Heth, “Remarriage for Adultery or Desertion,” 64.

[9] Wayne Grudem, Christian Ethics: An Introduction to Biblical Moral Reasoning (Wheaton: Crossway, 2018), 812; Keener, …And Marries Another. 39; Naselli, “What the New Testament Teaches,” 24.

[10] Intone-Brewer, Divorce and Remarriage in the Bible. 110, 113-14; Keener, …And Marries Another. 39; Naselli, “What the New Testament Teaches…,” 10.

[11] Intone-Brewer, Divorce and Remarriage in the Bible. 238-39. Instone-Brewer believes Joseph wanting to divorce Mary in a commendable manner (Matthew 1:19) shows the Hillel divorce was around earlier than some others believe.

[12] Intone-Brewer, Divorce and Remarriage in the Bible. 239.

[13] Intone-Brewer, Divorce and Remarriage in the Bible. 135, 239.

[14] Intone-Brewer, Divorce and Remarriage in the Bible. 135, 154.

[15] Intone-Brewer, Divorce and Remarriage in the Bible. 135.

[16] Keener, …And Marries Another. 38.

[17] Intone-Brewer, Divorce and Remarriage in the Bible. 154.

[18] Grudem, Christian Ethics. 812.

[19] Intone-Brewer, Divorce and Remarriage in the Bible. 153; Naselli, “What the New Testament Teaches…,” 24; Grudem, Christian Ethics. 812.

[20] Naselli, “What the New Testament Teaches…,” 24.

[21] Grudem, Christian Ethics. 833.

[22] Intone-Brewer, Divorce and Remarriage in the Bible. 134-35.

[23] See Appendix B for more about the minority view.

[24] Craig Blomberg, “Marriage, Divorce, Remarriage, and Celibacy: an Exegesis of Matthew 19:3-12,” Trinity Journal 11, no. 2 (1990): 162. D.A. Carson, “Matthew,” vol. 9 of The Expositor’s Bible Commentary Revised Edition, ed. Tremper Longman III and David Garland (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2010), 464-74; William Heth, “Jesus on Divorce: How My Mind Has Changed,” The Southern Baptist Journal of Theology 6, no. 1 (2002): 15; Heth, “Remarriage for Adultery or Desertion.” 73; Craig Keener, “Remarriage for Circumstances Beyond Adultery or Desertion,” in Remarriage After Divorce in Today’s Church: Three Views, ed. Mark Strauss, Counterpoints (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2006), 106-09; Robert Stein, “‘Is it Lawful for a Man to Divorce His Wife,’” JETS 22, no. 2 (1979): 117.

[25] Stein, “Is it Lawful.” 119-20.

[26] Keener, “Remarriage for Circumstances Beyond.” 106-09.

[27] Keener, “Remarriage for Circumstances Beyond.” 106

[28] Keener, “Remarriage for Circumstances Beyond.” 105-06. The topic of the indissolubility or dissolubility worthy a topic all by itself. However, key to viewing marriage as dissoluble is how one understands of the nature of marital and biblical covenants. On how/why marriage covenants can be broken: Heth, “Jesus on Divorce,” 17-20; Heth, “Remarriage for Adultery or Desertion,” 59-63. Instone-Brewer, Divorce and Remarriage in the Bible. 1-19.

[29] Keener, “Remarriage for Circumstances Beyond.” 104-06, 108, 117.

[30] Keener, “Remarriage for Circumstances Beyond.” 105-06.

[31] Keener, “Remarriage for Circumstances Beyond.” 104; Heth, “Remarriage for Adultery or Desertion,” 128.

[32] Heth, “Jesus on Divorce.” 15.

[33] Keener, “Remarriage for Circumstances Beyond.” 103.

[34] Keener, “Remarriage for Circumstances Beyond.” 109. Naselli, “What the New Testament Teaches…,” 24. Grudem, Christian Ethics. 781-82; Carson, “Matthew,” 472-473.

[35] Jay Adams, Marriage, Divorce, and Remarriage in the Bible: A Fresh Look at what Scripture Teaches (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 1980), 52.

[36] David Janzen, “The Meaning of Porneia in Matthew 5.32 and 19.9,” Journal for the Study of the New Testament 23, no. 80 (2001): 78-79.

[37] Harry Coiner, “Those Divorce and Remarriage Passages,” Concordia Theological Monthly 39 no. 6 (1968): 369. Carson, “Matthew,” 472.

[38] Heth, “Jesus on Divorce.” 16; Intone-Brewer, Divorce and Remarriage in the Bible. 143-144.

[39] Intone-Brewer, Divorce and Remarriage in the Bible. 143.

[40] Heth, “Jesus on Divorce,” 16.

[41] Heth, “Jesus on Divorce,” 16.

[42] Keener, “Remarriage for Circumstances Beyond.” 110.

[43] Keener, “A Response to Gordan J. Wenham,” in Remarriage After Divorce in Today’s Church: Three Views, ed. Mark Strauss, Counterpoints (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2006), 49.

APPENDIX 1: PERTINENT SYNOPTIC SCRIPTURES AND TERMS

The term “exception clause,” refers to the parts in both Matthew 5:32 and 19:9 that are bolded. The “prohibitive clause,” on the other hand, refers to the parts in each of the four scriptures that are underlined. The other clauses neither bolded nor underlined will not be examined because they are more closely associated with the subtopic of remarriage. Since this essay’s concern is with the synoptic gospels and explaining the seeming contradiction, other Bible passages that deal with marriage, divorce, and remarriage are not analyzed, such as 1 Cor. 7:10-16, 39.

The NIV is used for Mathew 5:32 as opposed to ESV because the NIV corrects how the verse is commonly mistranslated according to Naselli. Naselli was assistant editor of the 2015 NIV Zondervan Study Bible (Naselli, “What the New Testament Teaches…,” 18-19.).

APPENDIX 2: SUMMARY OF THE VIEWS ON DIVORCE AND REMARRIAGE

Interpreting the divorce exception in the synoptic gospels is typically broken down into three different but related sub-topics: whether the exception is valid at all, what the meaning of sexual immorality is, and whether the exception applies to remarriage or only divorce. This essay is concerned with addressing the first of those sub-topics. Based on the research done for this essay, it became apparent the most popularly held view is the majority view: divorce is permissible for the innocent spouse in situations of sexual immorality or abandonment, and if the divorce had just cause, then remarriage is also permissible. John Piper is likely the most prominent Protestant figure who currently holds the minority never-divorce, never-remarry view.[1] Gordon Wenham is the leading representative of the sometimes-divorce-but-never-remarry view.[2] Although research done for this essay was solely focused on the Protestant scholars, it should be noted the position of the Roman-Catholic church is that marriage is indissoluble.[3] Believing marriage is indissoluble leads to the never-divorce-never-remarry view. One final note worth mentioning is here is how the minority view tends to use Mark and Luke to interpret Matthew (5:32 and 19:9) and Paul (1 Cor. 7:15). Keener points out it should be the other way around; that the smaller number of texts that assume the exception (Mark and Luke) should be read in light of the larger number of texts with the exception (Matthew 5:32, 19:9, and 1 Cor. 7:15).[4]

[1] Naselli, “What the New Testament Teaches…,” 3-4, 14. See Naselli’s footnotes. Naselli is as familiar with the particulars of Piper’s argument than any, since Naselli is an elder at Piper’s church, professor at Piper’s seminary, and considers Piper to be a close friend and mentor. Naselli argues, respectively, that his mentor is incorrect.

[2] Gordon Wenham, “No Remarriage After Divorce” in Remarriage After Divorce in Today’s Church: Three Views, ed. Mark Strauss, Counterpoints (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2006), 19-42. Wenham, “Does the New Testament Approve Remarriage After Divorce?” Southern Baptist Journal of Theology 6, no. 1 (2002): 30-45. Wenham co-wrote a famous book with Heth [Heth and Wenham, Jesus and Divorce: Towards an Evangelical Understanding of the New Testament Teaching (London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1984)], but Heth changed his mind years later after being convinced by arguments by Keener and others. Heth outlines his shift in “Jesus on Divorce,” in-particular pages 4-5, 13. Wenham interprets the prohibitive clauses literally for remarriage but not literally for divorce because of how he interpreters the syntax of the exception clause. Wenham also primarily appeals to early church history, which is a weaker argument than primarily basing his argument on scripture. I recommend Instone-Brewer’s chapter on divorce through church history from the Protestant perspective (Divorce and Remarriage in the Bible, 238-67) which would disagree with Wenham’s take on how unified the early church fathers stood on the issue.

[3] J.M. Kunz, “Is Marriage Indissoluble?” Journal of Ecumenical Studies 7, no 2 (1970) 333-37.

[4] Keener, “Remarriage for Circumstances Beyond.” 51.

APPENDIX 3: SUMMARY OF SCENARIOS REGARDING ORIGINALITY

When faced head-on with the synoptic dilemma outlined at the start of this essay, a natural question one ought to ask is “did Jesus say it?” The question of whether the exception clause is original to Jesus or an insertion by Matthew is debated well from both sides by scholars, with some admitting either side could be correct. If the exception clause is original to Jesus, it certainly ends much if not all the debate whether the exception clause should be taken seriously. However, the approach taken intentionally in this essay is to show there is another way to show the validity of the exception clause even if Jesus hadn’t uttered it. If one is to take a literal approach to the prohibitive clause, one must come up with an explanation for why Matthew inserted the exception clauses, and either Matthew was incorrect or correct. Figure 3.A below summarizes the different broad interpretive options available to “solve” the synoptic dilemma.

The shaded row (option #2) is the view this essay hopes to successfully show is a legitimate interpretative option.[1] The blind spot of options #3 and #4 is they assume the exception clause hinges on originality. More specifically, options #3 and #4 assume if the exception clause is valid, Mark and Luke would have included it. What that assumption does not take into consideration is Mark and Luke could have had reason to omit the exception clause while still affirming it. In other words, just because Mark and Luke omitted it, doesn’t mean they disapproved of it. The same applies to Jesus. Jesus could have affirmed the exception clause without having to actually speak it. This is explained in the essay.

[1] Although I argue option #2 is a legitimate option, I specifically believe a combination of option #1 and #2 is possible. Such a combination would hold the Matthew 5:32 exception clause as original to Jesus because there is no parallel passage, whereas the 19:9 exception could more likely to be a Matthean insertion (Matthew 19:1-12 and Mark 10:2-12 are parallel passages). I would have liked to see scholars I researched address the uniqueness of Matthew 5:32 more. With option #2 being a legitimate view, as shown in this essay, it opens the door for the possibility of Matthew 5:32 being original to Jesus and Matthew 19:9 not being original to Jesus, yet still affirming the validity of the exception clause overall because originality is not required to validate the exception clause.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Adams, Jay. Marriage, Divorce, and Remarriage in the Bible: A Fresh Look at what Scripture Teaches. Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 1980.

Blomberg, Craig. “Marriage, Divorce, Remarriage, and Celibacy: an Exegesis of Matthew 19:3- 12,” Trinity Journal 11, no. 2 (1990): 161-96.

Carson, D.A.. “Matthew,” vol. 9 of The Expositor’s Bible Commentary Revised Edition. Edited by Tremper Longman III and David Garland. Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2010.

Coiner, Harry. “Those Divorce and Remarriage Passages,” Concordia Theological Monthly 39 no. 6 (1968): 367-84.

Grudem, Wayne. Christian Ethics: An Introduction to Biblical Moral Reasoning. Wheaton: Crossway, 2018.

Heth, William. “Jesus on Divorce: How My Mind Has Changed,” The Southern Baptist Journal of Theology 6, no. 1 (2002): 4-29.

Heth, William. “Remarriage for Adultery or Desertion.” Pages 59-83 in Remarriage After Divorce in Today’s Church: 3 Views of Counterpoints Church Life. Edited by Paul Engle and Mark Strauss. Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2006.

Instone-Brewer, David. Divorce and Remarriage in the Bible: The Social and Literary Context. Grand Rapids: Eerdman’s, 2002.

Instone-Brewer, David. Divorce and Remarriage in the Church: Biblical Solutions for Pastoral Realities. Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 2003.

Janzen, David. “The Meaning of Porneia in Matthew 5.32 and 19.9,” Journal for the Study of the New Testament23, no. 80 (2001): 66-80.

Keener, Craig. …And Marries Another: Divorce and Remarriage in the Teaching of the New Testament. Peabody: Hendrickson, 1991.

Keener, Craig. “Remarriage for Circumstances Beyond Adultery or Desertion.” Pages 103-19 in Remarriage After Divorce in Today’s Church: 3 Views of Counterpoints Church Life. Edited by Paul Engle and Mark Strauss. Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2006.

Naselli, Andrew. “What the New Testament Teaches about Divorce and Remarriage.” Detroit Baptist Seminary Journal24 (2019): 3-44.

Stein, Robert. “‘Is it Lawful for a Man to Divorce His Wife,’” JETS 22, no. 2 (1979): 115-21.

Wenham, Gordon. “Does the New Testament Approve Remarriage After Divorce?” Southern Baptist Journal of Theology 6, no. 1 (2002): 30-45.

Wenham, Gordon. “No Remarriage After Divorce” Pages 19-42 in Remarriage After Divorce in Today’s Church: 3 Views of Counterpoints Church Life. Edited by Paul Engle and Mark Strauss. Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2006.